The teaching of anatomy at medical schools in the traditional fashion has long been regarded as something of a rite of passage. Students could look forward to the day when they were introduced to their very own cadaver and embark on the journey of getting to know the human body. However at many medical schools, my own included, those days are long gone.

I arrived at medical school about six weeks ago now and I've already seen about seven dead bodies. I say about seven, it could have been more, could have been less. But since they were carved into smaller pieces it was hard to tell. Carved into smaller pieces so we, the future of the medical profession could prod them and have a poke around inside. Just after lunch too - nice!

This is, however, an increasingly rare scene. Medical schools are slowly phasing out the use of cadavers to teach anatomy. Recruiting, storing and maintaining dead bodies is an expensive business and, with a decrease in volunteers, there is no choice but to find alternatives.

The way that the bodies of deceased children were handled at Alder Hey hospital is still fresh in everybody's minds and that has certainly had an impact on the way anatomy is taught in medical schools. The number of people submitting themselves to this unique treatment after death has dropped and continues to fall.

Moreover there are increasing ethical and safety concerns around the holding and handling of dead human tissue, particularly with the continuing discovery of new and dangerous pathogens. HIV was a startling new discovery not that long ago remember. The legal and ethical obstacles are becoming too complex to be surmountable on a regular basis.

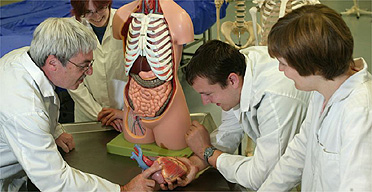

Now we use online resources, colouring-in books and models. You may laugh, but they do work. Once a person has died and been embalmed and their bodily fluids have been replaced with a preservative mixture, what remains bears more resemblance to a waxwork doll than a living breathing member of your family. This is what I'm telling myself anyway as I round a corner to be confronted with another fresh cadaverous specimen. The smell of the formalin mixture is quite overwhelming.

That's not to say cadavers don't have an important role to play in the teaching of doctors. Among other things they confront us with the issue of death, which is something that we all have to deal with sooner or later. I had certainly never seen a dead body before my day in the anatomy suite.

However there is also no getting away from the human aspect to this most clinical of processes. I look closer at the woman whose reproductive organs are revealed for me to see. I know from my previous life as an archaeologist that you can tell how many children a woman has had from the striations on her pubic bone where the muscle has snapped during childbirth. I look at this cadaver and I wonder how many children she had, how old they are and what they grew up to become. I wonder what her name is and what her life was like. Was she happy?

Clearly I should be concentrating on the technical name for that squishy bit just to the left of her ovary but I'm not. My classmates deal with the situation sensitively and handle the specimens with care, they ask intelligent questions and take care to cause no damage. Behaving with respect under these circumstances is of the utmost concern here.

Nobody in my class could fail to be moved by the amazing gift of their mortal remains that some generous person had given to us on their death. It was truly extraordinary to hold and see what remained of a human life.

Afterwards, I was noisily sick in the toilets. It was moving and amazing, I didn't say it was pleasant!